In conversation with

Tessa R. Groenewoud

Ghent, Belgium

Hi Tessa, please introduce yourself.

I live in Belgium and I am originally from The Netherlands. At the moment I live and work in Ghent, a small town near Brussels. I was trained as an artist, not as a photographer, but photography has always played some part in my life. Be that in my artistic work, as medium or as focus for research, or for jobs (I’ve been a concert photographer for an underground music magazine, for example, and currently I work for a dance school as their photographer and graphic designer, amongst other gigs).

My artistic work was installation-based for a long time. I used a variety of media of which photography (also analogue) was just one. I have been exploring working in the dark room for about 10 years, where I worked both on my artistic works as well as private prints. These private prints were hardly ever shown to anyone until quite recently, and this marked an important shift in my artistic work.

I never considered myself a “photographer” and I still don’t. I thought that my private, purely photographic work was not good enough, and I kept it to myself even though it’s been a consistent habit of mine since the age of 17. It was always a private visual diary, and I enjoyed experimenting with the pictures in secret in my dark room. It happened only occasionally that I would give a print to a close friend as a present.

After a kind of breakdown in my artistic and personal life, approximately 5 years ago, and a period of keeping a low profile as an artist, I made a shift and decided to focus mainly on my analogue photography and to come out with this work that is so deeply personal and close to me. I decided to invest and upgrade my equipment and darkroom setup. As a photographer I am self-taught.

What does analog photography mean to you? What excites / fascinates you about it?

With analogue photography, the attraction is multi-facetted. I’ve always been fascinated by the presence of images in society. People learned to produce and deal with images, literally and figuratively, through the lens of analogue photography; it was instrumental not only for professionals but also the general public. Over time, the process of creating pictures became more and more democratic, and by a certain point was a very popular and widely practiced pastime. This fascinates me from a historical and cultural perspective, even philosophically. The impact of photography, first analogue, later digital, has been enormous on the way we see, remember and classify. In my previous conceptual work this was something that often surfaced as an area of research.

On another level, I am kind of a nerd, and I really like its mechanical aspect. The part of it that is out of our hands. But also the magic of this invention of an eye that can capture and manipulate what and how and when we see. This puts a spell on me… The fact that it translates an innate and primal human feature that most people don’t even experience consciously — the act of seeing — into a kind of language dictated by the camera means that it’s both a way of deconstructing and confronting what, how, when and maybe also why we see.

And thirdly there’s the very elementary but oh so magical process of printing with chemicals — the origin of these material images — that makes them even more banal in a way, but is refreshing to me even after all these years.

In your opinion, what are the advantages and disadvantages of analogue photography?

In a purely practical sense, its disadvantages are of course the costs and the environmental impact—the waste of packaging, film and chemicals, and the inevitable use of water.

The advantage is the closer confrontation with the photographic process, which is more removed when working with digital, and this influences my work in a positive way. The distance, the moment, the machine, the print,… it’s all so much more pronounced with analogue, and at this point an essential aspect of why I do what I do. And I have to admit, there is also a romantic element to it which is part of the attraction for me. Something profoundly elementary, inherent to the photographic process, is that you need both light and darkness.

Do you concentrate on a certain topic in your work?

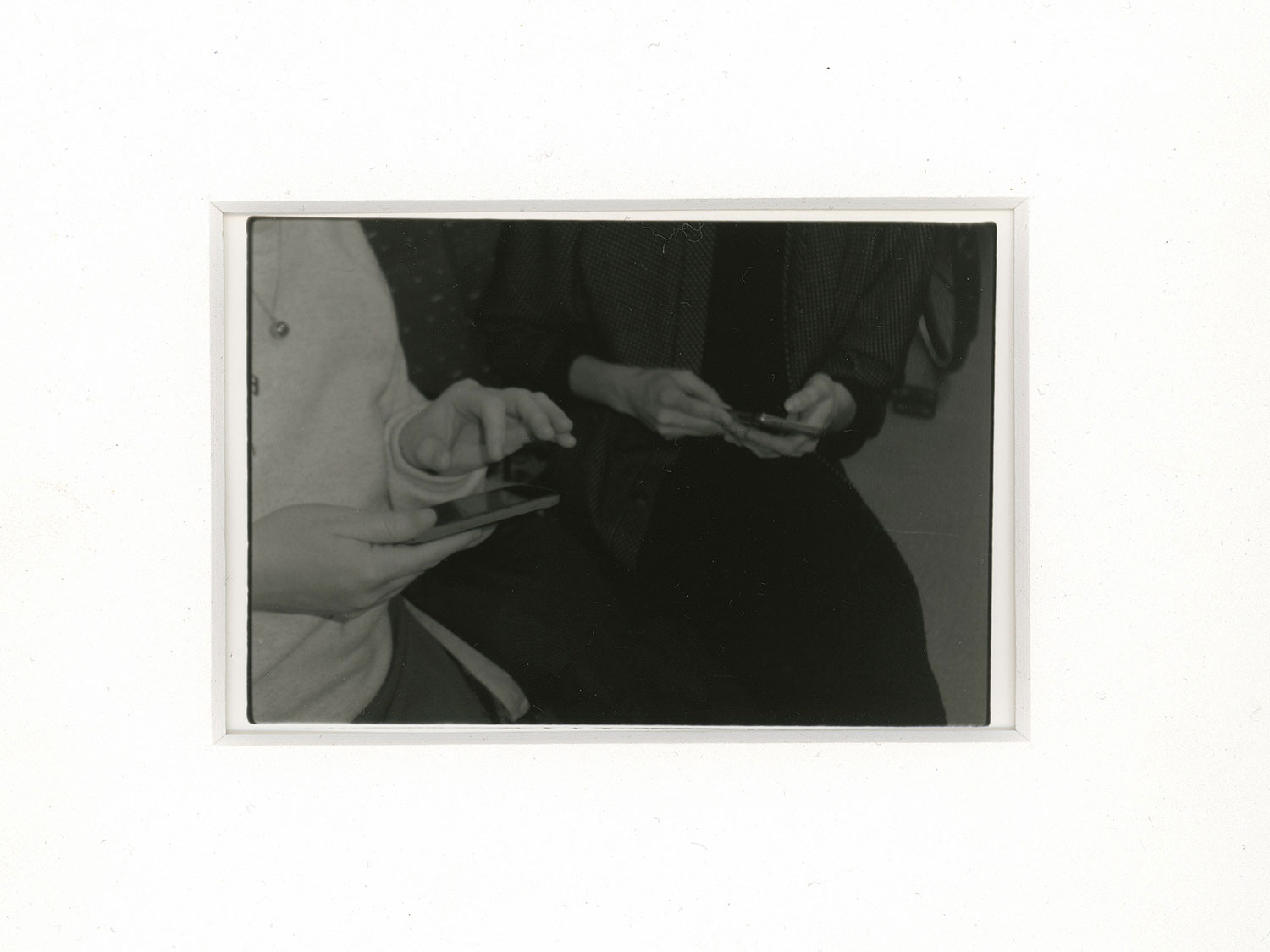

My work at this point is built upon a growing collection of fragments from my life. I have different cameras loaded and ready to use in different places (my studio and my home) and I take them when I visit friends, go for walks, travel, or when I am alone in the house or studio. The images I make are often captured quite spontaneously. When I photograph people (my friends) I always ask if I can take the picture. I am very aware of the invasive aspect of taking a picture (I don’t like to be in pictures myself in fact) but usually they trust me and consent.

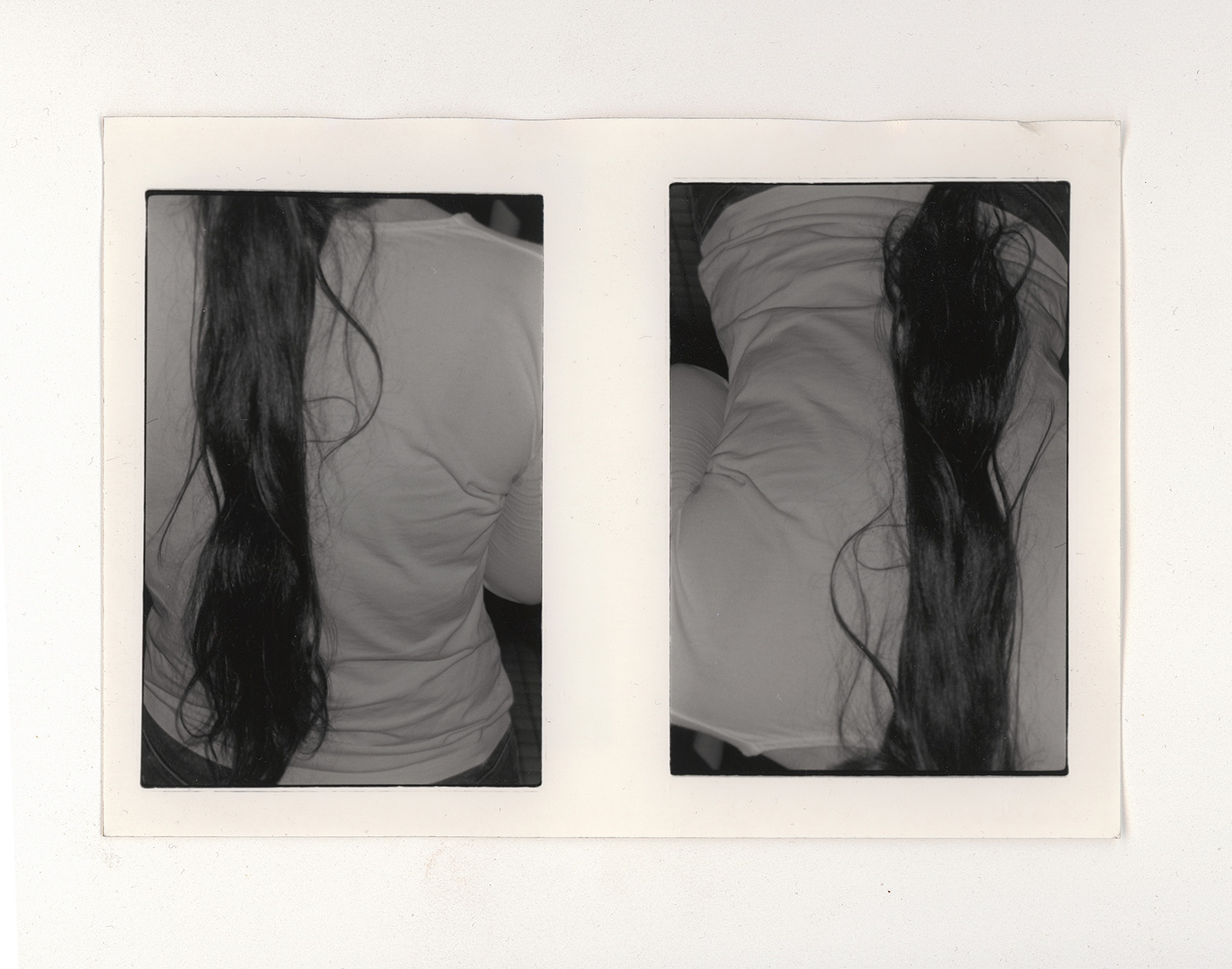

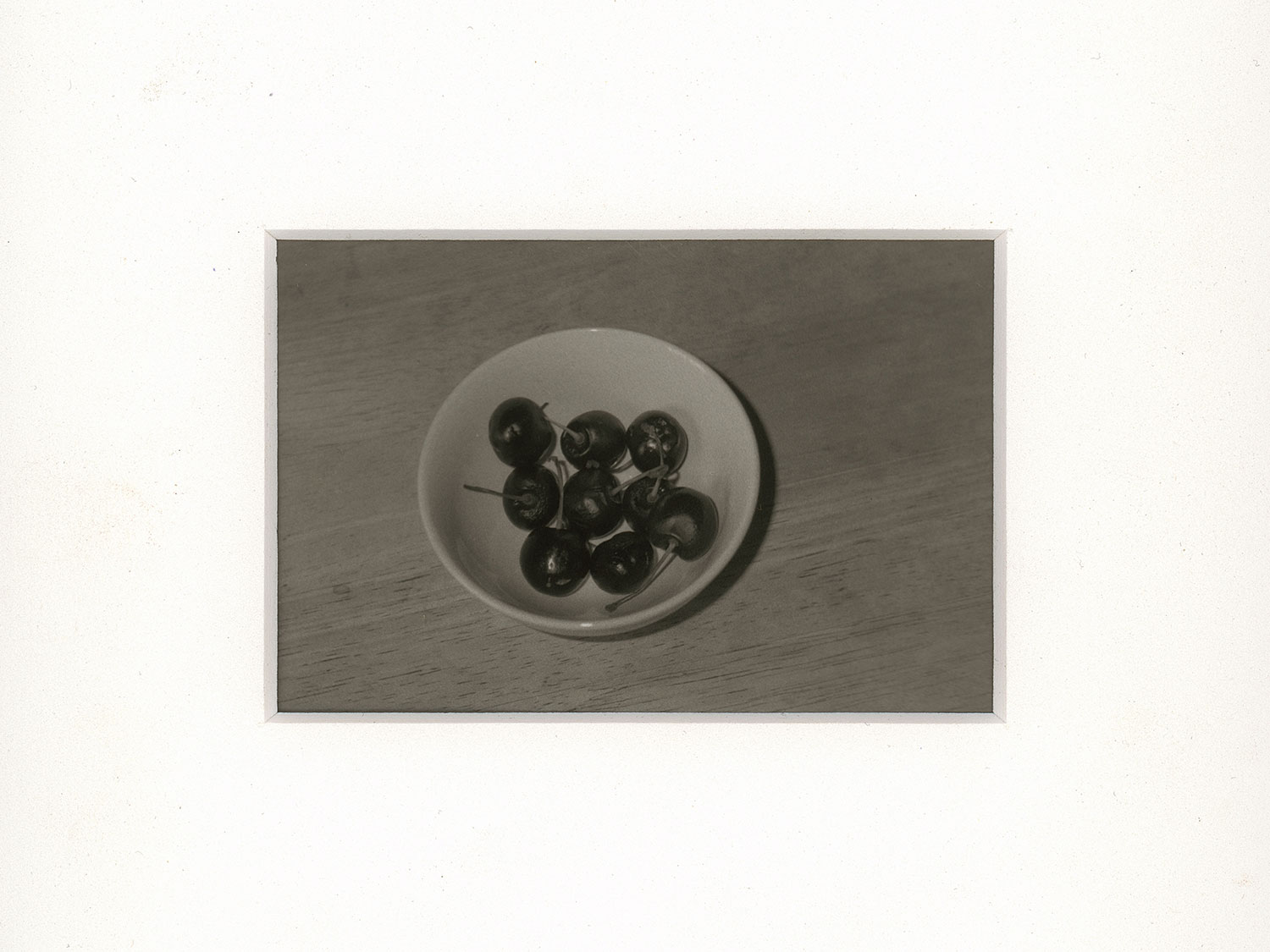

Other things I capture can be quite banal: a discarded corner of something, an abstract, overlooked little detail, an ordinary chair or an unappealing plant. I can also get seduced by aesthetics. Light is so elementary for seeing; when it becomes a shape before your eyes, it’s hard to resist trapping it and making it your own for a moment.

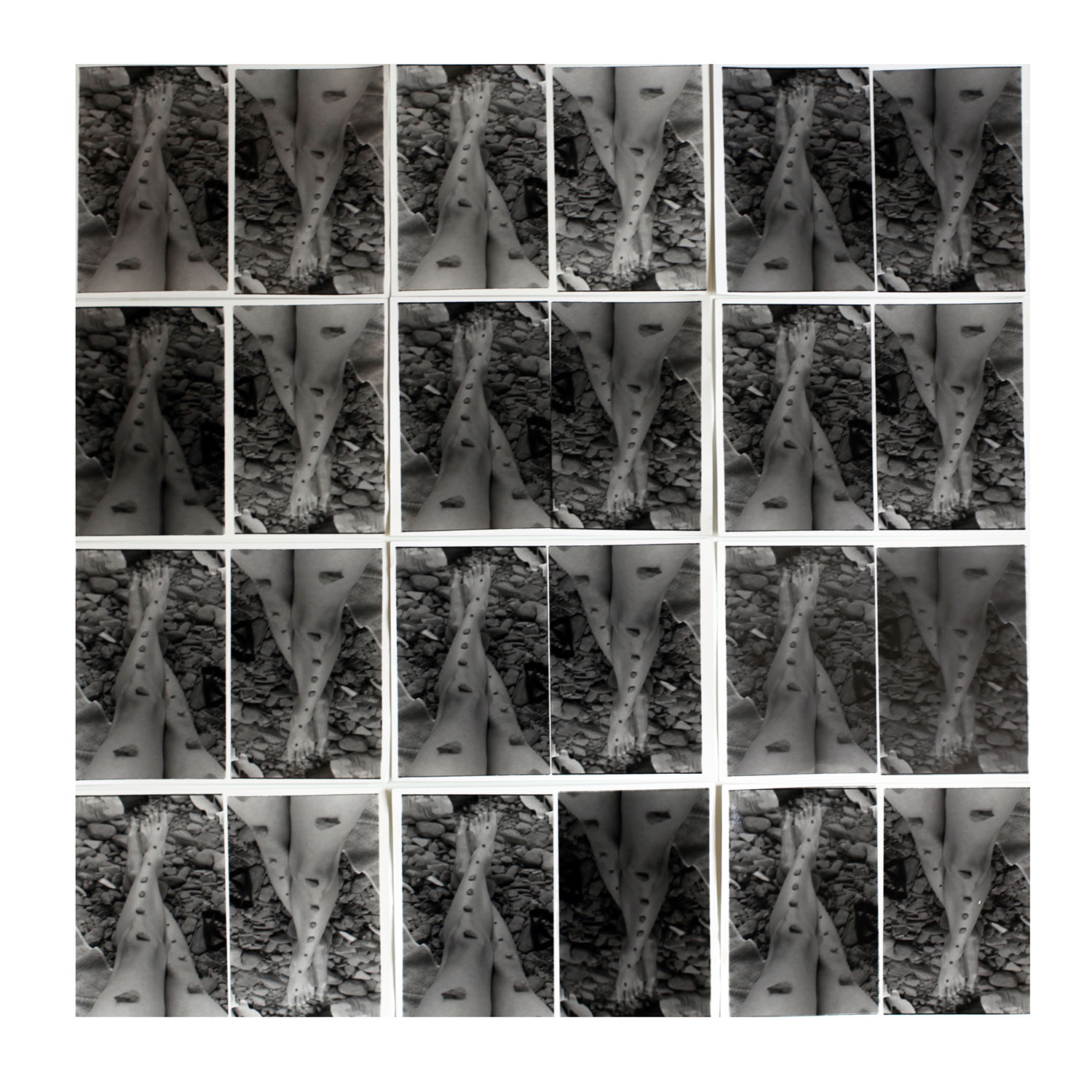

What I mean to say is that I don’t have a certain topic, but all my work is naturally closely related to me. It’s in the process of printing and manipulating that I create a distance, and by this time the original moment and depiction sometimes becomes a mere building block, like the paper and the chemicals, to be reworked into something more formal. Then I start to deconstruct or emphasize or repeat or cut and the images can become patterns or abstractions. In this way I like to think that photography itself becomes the main topic of my work.

Are there (analogue) photographers who have influenced your aesthetic and approach?

There are a lot of photographers that I like, but I am more influenced by filmmakers and by artists that sometimes use photography but aren’t considered photographers. Important to me is the work of Agnes Varda, Michael Snow, Chris Marker, Johan van der Keuken and Chantal Akerman, to name a few.

Do you have certain cameras and films that you prefer to work with?

I own several 35 mm cameras and one 6×9 Bessa Voigtlander that used to belong to my grandfather, and a Polaroid camera. I would like to explore working with medium format in the near future, but I like the straightforwardness of small cameras, easy to use and to take with you. Preferably not too expensive so I don’t have to worry so much about taking them out when it happens to rain a bit, or when I am in an otherwise less than ideal location. The cameras I use are reliable, straightforward, easy to use, and in a sense become an extension of me.

The films I use are not the fanciest ones. I don’t care much for that. I often like to keep it simple when it comes to that aspect. When I like something I tend to stick with it. Like Ilford PAN and Kodak Ultramax, which are good enough for me. I use them all the time.

Speaking of films: What does your workflow look like?

I have my film developed for me. I finally did it myself not too long ago, after years of postponing, and it’s easy enough, but I don’t really care for this step of the process; I get stressed out, worrying that I might be careless or clumsy for a moment and lose my images. What is important to me is the printing.

I regret so much that I can’t print my color shots the way I do my black and white. After I get the film, I select images on the basis of a scan. In the past I liked to get proofs from the lab, more frequently than I’m able to now, and I use(d) them as a first step in visualizing my negatives instead of a scan, but it’s quite expensive and lately it’s been necessary to save on costs. I prepare color prints digitally before having them printed at a lab. As for the black and white prints (which are what I use most frequently), I process them in a purely analogue way in my dark room, except for the occasional poster edition that I get printed elsewhere.

What advice would you have for other photographers who are reading this interview?

Do what you feel you have to do. And as a friend of mine once advised (about a different topic, but it works here too) – do what makes you feel alive!

If you publish your work on Instagram: curse or blessing?

It’s nice to get a certain visibility, which is what it’s good for. I postponed creating an account for a long time, and only started one quite recently (two years ago). I use it, but I am very weary of algorithms and big companies, as well as the bite-size aesthetic fast sauce that we all flatten our awareness with.

Which 3 photo books can you recommend / should you definitely own?

“Foto en Copyright” (G.P. Fieret), “Youth Is an Art” (Daan van Golden) and “Fotografià” (Soll LeWitt)

Thank you so much for your time!

Favorites

Nikon F3, Contax TVS, Praktica Super TL3, Bessa Voightlander, Polaroid 635, Nikon FM

Ilford Pan, HP5 Plus, Kodak Ultramax, Kodak Ektachrome E100

Color